The Mean Value Theorem

Out of all mathematics that I’ve studied, I would say the most interesting subject that I find is without a doubt, analysis. I find my fancy quite inevitable: the history of analysis can be seen as the history of physics itself, from Newton’s description of all of motion through differential equations to Einstein’s formulations of gravity via differential geometry. Despite a person who understands only parts of it, I find the ideas irresistable to the say the least. I could shed tears just by thinking of the beauty!

Today, rather than focusing on the physics, however, I would like to introduce you to another part about the field of analysis that I love: it’s thoroughness. By looking into the fundamental tools that humanity has devised to tackle and triumph in proving the intuitive, one cannot but be amazed. Personally, I am quite the geometric guy; I like to visualise and “see” what I’m dealing with. In this sense, I would like to introduce you to one of my favourite tools that has undeniable power that prevails throughout calculus: the mean value theorem.

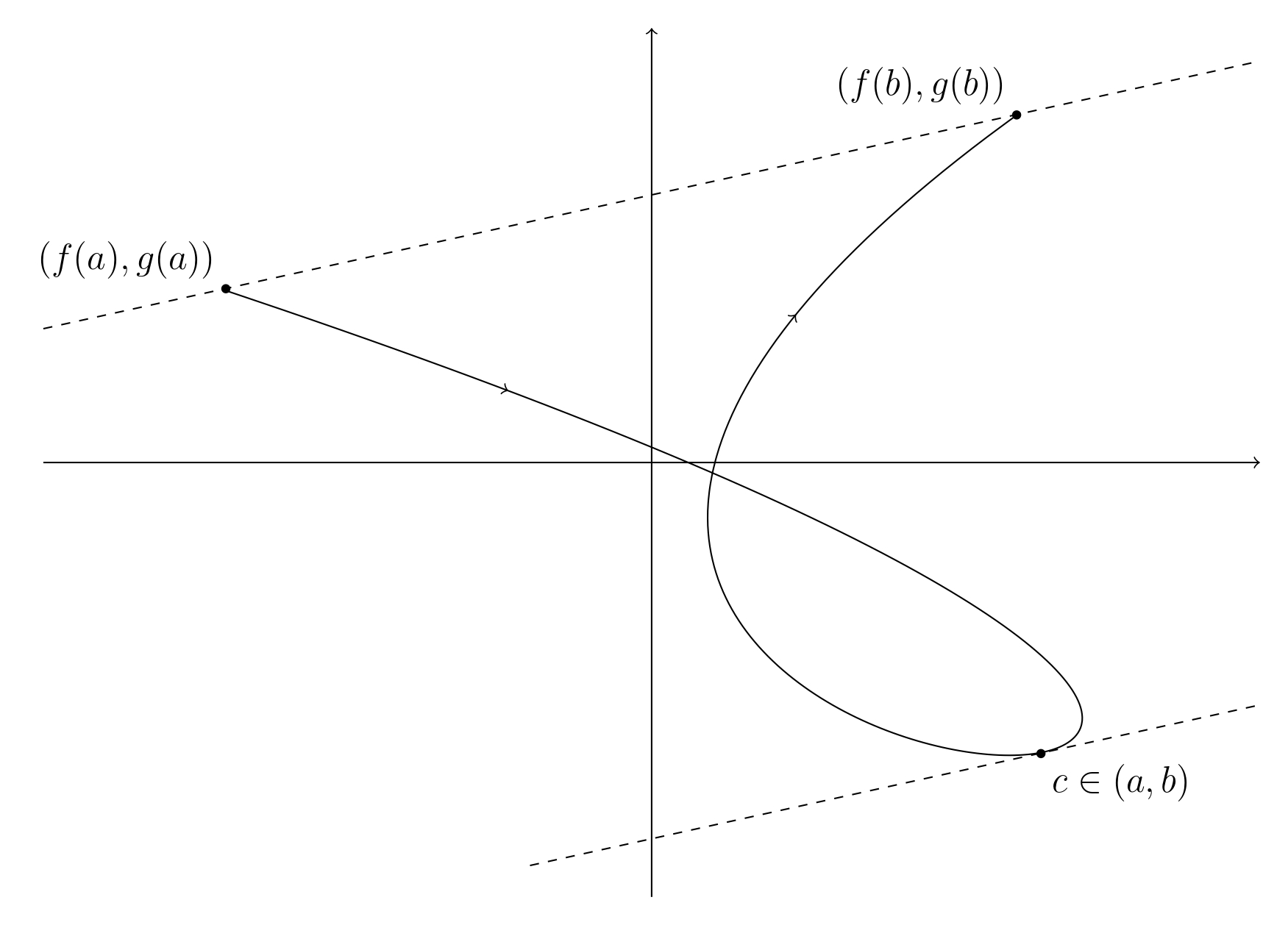

Imagine a single curve, described by a functions \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) and \(g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) of a single parameter \(t\).

It is quite easy to imagine how there would always be a point \(t\) on the curve whose gradient would be parallel to the line that connects the two endpoints. This is the basis of what we call Cauchy’s mean value theorem (or the generalised mean value theorem).

$$\frac{f'(c)}{g'(c)}=\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{g(b)-g(a)}$$

(aforementioned, there exists a point whose infinitesial slope equals the slope of line that connects the two endpoints)

The useful of this equation comes from the fact that it easily relates functions with it’s derivatives, prevailent in analysis. One of its most astonishing uses, to me personally, is how its used to prove the seemingly unprovable Taylor’s theorem with the remainder. In first year calculus, physics and math students alike, everybody sees the theorem takes it as some sort of impeccability, something that is so often used but is seemingly impossible to grasp one’s head around. However, we can provide a quite clear-cut proof using Cauchy’s mean value theorem from above, providing us freedom from the negligence we once dealt this theorem with.

Let us first present the theorem with the remainer in all its glory. Taylor’s theorem with the remainder states that any function that is differentiable \(k+1\) times on \((a,x)\) with the \(k\)-th derivative continuous on \([a,x]\) can be expressed as a sum like the following.

$$f(x)=T_n(x)+R_n(x)$$

with

$$T_n(x)=\sum^n_k=0\frac{f^{(k)}(a)}{k!}(x-a)^k\hspace{1cm}R_n(x)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(a)}{(n+1)!}(x-a)^{n+1}$$

The proof starts with stating that the two parameterised functions that are to be inputted to Cauchy’s mean value theorem.

$$F(t)=f(x)-\sum^n_{k=0}\frac{f^{(k)}(a)}{k!}(t-a)^k\hspace{1cm}G(t)=\frac{f^{(n+1)}(a)}{(n+1)!}(t-a)^{n+1}$$

Carefully choosing the two points to be evaluated between to be \(a=a\) and \(b=x\),

$$\frac{F'(c)}{G'(c)}=\frac{-\sum^n_{k=0}\frac{f^{(k+1)}(a)}{k!}(c-a)^k-\sum^n_{k=0}\frac{f^{(k)}(a)}{(k-1)!}(c-t)^{k-1}}{(n+1)(c-a)^n}$$

and

$$\frac{F(x)-F(a)}{G(x)-G(a)}=\frac{f(x)-\sum^n_{k=0}\frac{f^{k}(a)}{k!}(x-a)^k}{(x-a)^{k+1}}$$

where equating the two expressions result in the Taylor’s theorem with the remainder that we stated above!!